Trade Roots: The Macaw Chronicle

Read the Taos Book Review of the Macaw Chronicles

*Excerpt (pages 1 - 5)

It’s early December 1972 and while making preparations to head south in search of the mysterious and by now almost mythical macaw, Ricardo and I drive over to Zuñi for the annual Shalako ceremonies. Zuñi Pueblo is in western New Mexico near the Arizona state line and is home to an intricate and complex annual winter solstice rite that is both a traditional house blessing ceremony and an opportunity to offer prayers for the year ahead. We are guests of resident trader Richard Dodson and his wife Charlotte. Richard is a third or maybe fourth-generation trader, operating a trading post called Halona Plaza which has been in his family since the late nineteenth century. The mood at the Dodson home in the middle of Zuñi Village is one of intense anticipation. Probably twenty or thirty hippie/beatnik types have found their way to his house where, in the classic Pueblo tradition, no one is refused shelter and everyone is fed. With a pot of peyote tea simmering on the stove, the amazing night of my first Shalako begins to unfold.

Imagine a musical extravaganza lasting fourteen hours where hundreds of costumed participants dance and pray simultaneously at seven different locations. Preparation for this spectacular ceremony takes twelve months and includes numerous other symbolic ritual activities throughout the year. The support group to choreograph all of these activities consists of several thousand people. This annual ritual is called Shalako and is said to be the oldest continually performed religious ceremony in North America.

Each year several new homes—usually six Shalako, a Mudhead and a Longhorn house—are built in the pueblo with all the labor contributed by village members, a practice ensuring village growth. Some of the community members with major responsibilities have received their appointments from various village headmen while other positions have to do with family lineage. It seems as though everyone knows their job without any exchange of instructions. Those chosen for “Mudhead Duty” must work for the entire year serving the community by building the houses for the ceremony without pay and depending on the community to feed them.

To give you a true sense of what Shalako means to me, I have to jump ahead several years to 1976. By then I’ve attended several Shalako ceremonies but still am a youthful observer with only an elementary understanding of the ritual’s complex significance. By now I’m living in McKinley County, less than a couple kilometers from the border of Zuni land. This early December afternoon is unusually cold and cloudy and the damp chill forecasts snow. I drive my old ‘65 Chevy pickup the twenty miles over to Zuñi Pueblo from my home in Ramah, New Mexico, hoping to do a little trading.

The village is bustling with activity, preparing for the annual solstice ceremony. Quite a few pickups are lined up in front of my friend Jajulalita Lamy’s house and several trucks have live sheep roped together in back. Smoke is pouring from both chimneys as Jajulalita greets me at the door with a smile and I feel the high energy spilling from the house. Instead of inviting me inside her home as she usually does, she motions me to follow her to the shed around back. Jajulalita opens the door to the shed and as I cross the threshold I enter another reality—a very crowded reality filled with the smell of blood and death. The room is about eighteen-by-eighteen feet with a roaring fire in the big wood-burning stove in the center. The temperature must be 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Maybe forty people and twenty or thirty sheep are crowded into this small space. Jajulalita laughs at the shocked expression on my face and asks if I will help her family prepare for the evening feast. In a daze I agree and she leaves me standing here observing the scene before me.

Young men are brandishing bloody knives and the sheep are in various stages of slaughter. The heavy smell of death is stomach-turning and I try not to breathe. All I can hear is the gurgling sound of bleating sheep whose throats are being cut, their blood pumping out with every heartbeat. The old women are helping by carefully removing the organs and preparing the meat for cooking. It occurs to me that I never knew what death really smelled like until now. A young man motions to me with a casual wave of his bloody knife-wielding hand and with few words he gives me a choice of several knives while another fellow hands me a rope with a sheep attached to the other end. The sheep is bleating, speaking to me and almost pleading, maybe sensing that I have been a vegetarian for the last few years.

I sit on a stool with the sheep between my legs, its back toward me. I lift his head and pull it toward me then reach around to the exposed neck and begin to draw my knife across its jugular vein. The knife feels awfully dull and it doesn’t seem to want to penetrate the skin. My sheep is not jumping around or squirming and in fact is very calm, just softly bleating. My hands feel weak, but finally I muster the strength to draw blood and begin to cut with a sawing motion. I try to finish quickly, but somehow I’ve entered a surreal time zone where everything is moving very slowly, and I can see that my sheep’s death may take a very long time. It remains docile as I keep cutting. Blood begins to flow down its neck and the gurgling sound is like a babbling brook. In my mind’s eye, I see water moving over rocks while I continue to cut my sheep’s throat in this timeless space I have entered. With each breath there is a gurgling bleat and a little more blood pumps out the jugular. In this small room, bustling with activity, I am alone with my sheep. Finally, I’ve cut enough that I know my sheep has irrevocably passed on to another world while its body waits to feed the stew pot.

As I finish this initial phase of slaughter, a tiny Zuñi grandmother comes over to show me what to do next. I make an incision down the abdomen from the neck to the anus and around the arms and legs. She warns me to be careful not to puncture any of the organs and helps me to separate the coat from the corpse. By carefully holding onto a flap of skin and using the knife to cut the layer of fat under the skin I’m able to free the skin from the body, rather like removing a sweater. I silently say to myself sheep, wool, sweater.

I’m almost enjoying the methodical and systematic movements of this procedure even though it seems to be taking quite a while, but I am in that timeless zone, so who really knows? I’m even getting used to the smell as I watch the old lady expertly remove the organs, leaving a carcass ready to be cut up. When I finally finish I go outside and stand in the hazy, late afternoon sunlight. I feel lightheaded and almost sorry to leave, and although I am deeply breathing in the cold fresh air I feel slightly confused and isolated. The absence of ego and the way everyone worked together, the youngest men and the oldest women, has given me a sense of a unity lacking in my own personal experience.

Still wobbly I get into my truck and head toward the Zuñi River where a crowd has gathered behind Halona Plaza, the old trading post. Several Zuñi as well as a handful of Anglos are talking quietly among themselves. I see a few acquaintances and nod, still too dazed to want to engage in conversation. What could I really say? How could I explain where I have been for the last few hours and how the deepest part of my consciousness has been radically altered?

But now everyone is alert and looking to the west, and although still distant I can hear the clearly identifiable sounds of approaching dancers. There’s the shuffling jangle of bells, leg rattles made of turtle shells clacking as the attached deer hooves hit against them, hand-held gourd rattles filled with pebbles from red ant hills, all shifting and shaking as the dancers make their ceremonial entry to the village and move toward the Zuñi River.

Soon the elaborate entourage is in sight and the Shalako, couriers of the rain deities, walk into the village to bless the new homes. The little fire god (Shulawitsi) leads, followed by the rain priests of the north and south (Saiyatasha and Hututu). They’re surrounded and protected by the warriors of the six directions, the Salimopia, the many-colored warriors of the zenith, serving as guards. The Salimopia are swinging bullroarers to keep plenty of space between the Shalakos and the public and to punish ceremonial transgressions.

Each Shalako is over ten feet tall, its headpiece a mantle of twenty-inch red and blue macaw tail feathers framed by eagle plumes. There is a large clustered bunch, almost a bouquet, of dozens of smaller yellow, red, blue and green fluffy macaw and other parrot body feathers on top of their heads. Around the Shalako’s neck, just below its beak, are several turquoise and jacla bead necklaces, and each Shalako is wrapped in a traditional cotton shawl. The sight is truly extraordinary. I feel that I have somehow fallen down a rabbit hole, gone through a portal, and emerged in another dimension….To Be Continued

*Excerpt (pages 1 - 5)

Shalako Ceremony at Zuñi

It’s early December 1972 and while making preparations to head south in search of the mysterious and by now almost mythical macaw, Ricardo and I drive over to Zuñi for the annual Shalako ceremonies. Zuñi Pueblo is in western New Mexico near the Arizona state line and is home to an intricate and complex annual winter solstice rite that is both a traditional house blessing ceremony and an opportunity to offer prayers for the year ahead. We are guests of resident trader Richard Dodson and his wife Charlotte. Richard is a third or maybe fourth-generation trader, operating a trading post called Halona Plaza which has been in his family since the late nineteenth century. The mood at the Dodson home in the middle of Zuñi Village is one of intense anticipation. Probably twenty or thirty hippie/beatnik types have found their way to his house where, in the classic Pueblo tradition, no one is refused shelter and everyone is fed. With a pot of peyote tea simmering on the stove, the amazing night of my first Shalako begins to unfold.

Imagine a musical extravaganza lasting fourteen hours where hundreds of costumed participants dance and pray simultaneously at seven different locations. Preparation for this spectacular ceremony takes twelve months and includes numerous other symbolic ritual activities throughout the year. The support group to choreograph all of these activities consists of several thousand people. This annual ritual is called Shalako and is said to be the oldest continually performed religious ceremony in North America.

Each year several new homes—usually six Shalako, a Mudhead and a Longhorn house—are built in the pueblo with all the labor contributed by village members, a practice ensuring village growth. Some of the community members with major responsibilities have received their appointments from various village headmen while other positions have to do with family lineage. It seems as though everyone knows their job without any exchange of instructions. Those chosen for “Mudhead Duty” must work for the entire year serving the community by building the houses for the ceremony without pay and depending on the community to feed them.

To give you a true sense of what Shalako means to me, I have to jump ahead several years to 1976. By then I’ve attended several Shalako ceremonies but still am a youthful observer with only an elementary understanding of the ritual’s complex significance. By now I’m living in McKinley County, less than a couple kilometers from the border of Zuni land. This early December afternoon is unusually cold and cloudy and the damp chill forecasts snow. I drive my old ‘65 Chevy pickup the twenty miles over to Zuñi Pueblo from my home in Ramah, New Mexico, hoping to do a little trading.

The village is bustling with activity, preparing for the annual solstice ceremony. Quite a few pickups are lined up in front of my friend Jajulalita Lamy’s house and several trucks have live sheep roped together in back. Smoke is pouring from both chimneys as Jajulalita greets me at the door with a smile and I feel the high energy spilling from the house. Instead of inviting me inside her home as she usually does, she motions me to follow her to the shed around back. Jajulalita opens the door to the shed and as I cross the threshold I enter another reality—a very crowded reality filled with the smell of blood and death. The room is about eighteen-by-eighteen feet with a roaring fire in the big wood-burning stove in the center. The temperature must be 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Maybe forty people and twenty or thirty sheep are crowded into this small space. Jajulalita laughs at the shocked expression on my face and asks if I will help her family prepare for the evening feast. In a daze I agree and she leaves me standing here observing the scene before me.

Young men are brandishing bloody knives and the sheep are in various stages of slaughter. The heavy smell of death is stomach-turning and I try not to breathe. All I can hear is the gurgling sound of bleating sheep whose throats are being cut, their blood pumping out with every heartbeat. The old women are helping by carefully removing the organs and preparing the meat for cooking. It occurs to me that I never knew what death really smelled like until now. A young man motions to me with a casual wave of his bloody knife-wielding hand and with few words he gives me a choice of several knives while another fellow hands me a rope with a sheep attached to the other end. The sheep is bleating, speaking to me and almost pleading, maybe sensing that I have been a vegetarian for the last few years.

I sit on a stool with the sheep between my legs, its back toward me. I lift his head and pull it toward me then reach around to the exposed neck and begin to draw my knife across its jugular vein. The knife feels awfully dull and it doesn’t seem to want to penetrate the skin. My sheep is not jumping around or squirming and in fact is very calm, just softly bleating. My hands feel weak, but finally I muster the strength to draw blood and begin to cut with a sawing motion. I try to finish quickly, but somehow I’ve entered a surreal time zone where everything is moving very slowly, and I can see that my sheep’s death may take a very long time. It remains docile as I keep cutting. Blood begins to flow down its neck and the gurgling sound is like a babbling brook. In my mind’s eye, I see water moving over rocks while I continue to cut my sheep’s throat in this timeless space I have entered. With each breath there is a gurgling bleat and a little more blood pumps out the jugular. In this small room, bustling with activity, I am alone with my sheep. Finally, I’ve cut enough that I know my sheep has irrevocably passed on to another world while its body waits to feed the stew pot.

As I finish this initial phase of slaughter, a tiny Zuñi grandmother comes over to show me what to do next. I make an incision down the abdomen from the neck to the anus and around the arms and legs. She warns me to be careful not to puncture any of the organs and helps me to separate the coat from the corpse. By carefully holding onto a flap of skin and using the knife to cut the layer of fat under the skin I’m able to free the skin from the body, rather like removing a sweater. I silently say to myself sheep, wool, sweater.

I’m almost enjoying the methodical and systematic movements of this procedure even though it seems to be taking quite a while, but I am in that timeless zone, so who really knows? I’m even getting used to the smell as I watch the old lady expertly remove the organs, leaving a carcass ready to be cut up. When I finally finish I go outside and stand in the hazy, late afternoon sunlight. I feel lightheaded and almost sorry to leave, and although I am deeply breathing in the cold fresh air I feel slightly confused and isolated. The absence of ego and the way everyone worked together, the youngest men and the oldest women, has given me a sense of a unity lacking in my own personal experience.

Still wobbly I get into my truck and head toward the Zuñi River where a crowd has gathered behind Halona Plaza, the old trading post. Several Zuñi as well as a handful of Anglos are talking quietly among themselves. I see a few acquaintances and nod, still too dazed to want to engage in conversation. What could I really say? How could I explain where I have been for the last few hours and how the deepest part of my consciousness has been radically altered?

But now everyone is alert and looking to the west, and although still distant I can hear the clearly identifiable sounds of approaching dancers. There’s the shuffling jangle of bells, leg rattles made of turtle shells clacking as the attached deer hooves hit against them, hand-held gourd rattles filled with pebbles from red ant hills, all shifting and shaking as the dancers make their ceremonial entry to the village and move toward the Zuñi River.

Soon the elaborate entourage is in sight and the Shalako, couriers of the rain deities, walk into the village to bless the new homes. The little fire god (Shulawitsi) leads, followed by the rain priests of the north and south (Saiyatasha and Hututu). They’re surrounded and protected by the warriors of the six directions, the Salimopia, the many-colored warriors of the zenith, serving as guards. The Salimopia are swinging bullroarers to keep plenty of space between the Shalakos and the public and to punish ceremonial transgressions.

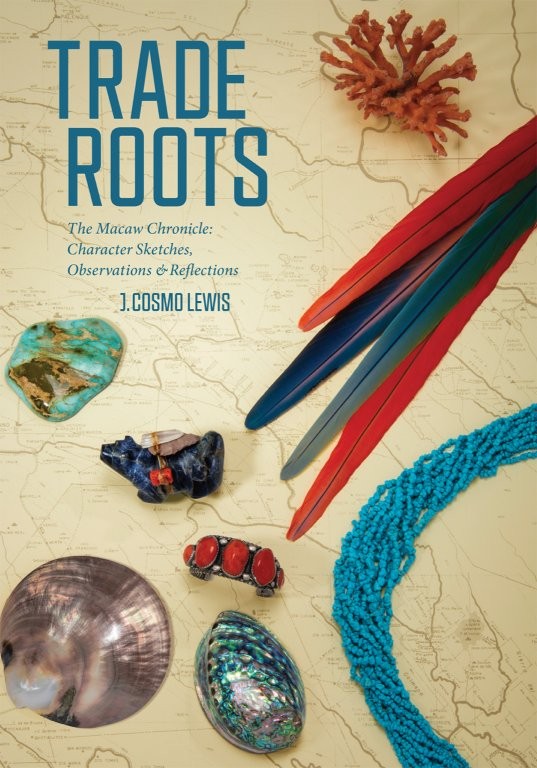

Each Shalako is over ten feet tall, its headpiece a mantle of twenty-inch red and blue macaw tail feathers framed by eagle plumes. There is a large clustered bunch, almost a bouquet, of dozens of smaller yellow, red, blue and green fluffy macaw and other parrot body feathers on top of their heads. Around the Shalako’s neck, just below its beak, are several turquoise and jacla bead necklaces, and each Shalako is wrapped in a traditional cotton shawl. The sight is truly extraordinary. I feel that I have somehow fallen down a rabbit hole, gone through a portal, and emerged in another dimension….To Be Continued